Shift to transactional-arts.com

May 23, 2011

Dear all,

there is now a newer, better, updated 🙂 website on transactional arts, let’s be in touch there:

Looking forward to hear from you,

best,

Daniela

Transactional Arts – Interaction as Transaction

November 3, 2009

Daniela Alina Plewe

National University of Singapore, Communications and New Media Program and University Scholars Program

Sorbonne 1, LAM – Laboratoire des Arts et des Médias

danielaplewe@gmail.com

Daniela Alina Plewe

Transactional Arts – Interaction as Transaction

A Form of Interactive Art

Abstract

Interactive media, especially the internet, are often used in an economic context where interactions are actually transactions. We focus on artists who apply economic principles and coin those works as “transactional arts”. We will observe that many accomplished new media works actually have transactional features and that the characteristics of the internet economy seem to facilitate this kind of art form.

In the field of transactional arts, buying and selling are means of self-expression, marketplaces are created as a form of art, mesh-ups may resemble online businesses and most importantly, incentives become artistic material. Often a kind of deal-making is involved and transactional art works therefore appeal to some sort of rationality.

Transactional artists actually apply economic know-how and therefore create not only aesthetic value but in many cases also economic capital. They therefore tend to fulfill success criteria of both disciplines involved – here art and business.

Keywords: Interactive Art, Transactional Art, Aesthetics of New Media

Transactional Art

We will concentrate on art, where a transaction is explicitly part of the work. With the following overview of transactional art we will not only introduce works” which make money” but any kind of art where some sort of value is explicitly exchanged. Often these values are financially viable.

The art-scene and the business world are two fields of society which tend to be not very intertwined. Of course there are all sorts of businesses with art, i.e. the art business and the art market where the two domains touch each other. However, we will not refer to the commercial activities related to the art market. Under the notion of transactional art we will also not address to the body of artworks, which reflects economic concepts in a broader sense, e.g. painting of money, sculptures in gold etc.

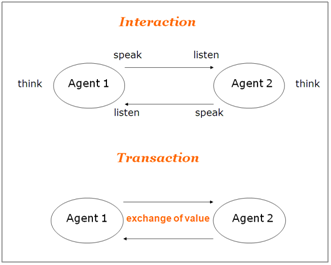

The Transactional Component – from Interaction to Transaction

A basic form of interaction may be defined as a kind of cybernetic loop in which two agents (human or systems) reciprocally listen, speak and think (Crawford 2002). This simplistic concept of interaction based on the sender-recipient model corresponds with the understanding of a cybernetic loop. We will use the cybernetic nature of both, interaction and transaction to draw a parallelism between the two.

1. Interaction and Transaction

In the field of transactional art we will observe a variety of combinations of these constituents.. Agents may vary: in the artistic context the transactions can involve as agents the artist, the audience, but possibly also subcontractors or contingent market-participants. The settings of the transactions may also be different. Some may take place within the art world, others involve the commercial domain and some artists even create their own marketplaces. In this sense transactional arts stand in the tradition of art-forms taking place in the social sphere, often involving all sorts of collaborations.

There is a variety of approaches to interactivity, which all seem compatible with the above over all structure. For example, Sally Mc Millian (2002) refines this scheme and differentiates between user-to-user, user-to-document (static information) and user-to-system (involving a strong algorithmic component) interactivity and defines then the relative position of freedom and control between human and machine agents.

The notion of interactivity has also been reflected in the field of aesthetics, especially in the context of interactive art. Nicolas Bourriaud (2002, p 112) introduces the concept of relational aesthetics as a “set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space.” He emphasizes the human-to-human aspect and refers to artworks, which explicitly create social events.

In his explorations on the aesthetics of interactive art, Jean-Luc Boissier (2002, online) considers relations (and relationships) as its genuine determinants. Despite the openness of interactive art, “to all sorts of particular states” this genre of art is “uniquely determined by the functionalities it offers”. The particular states one may interpret as possibility spaces, i.e. a feature of non-linear media referring to the sum of all variations and states of the technical system in which the artwork may appear. Manovich (2001) addressed this idea with the concept of “variability” as a genuine characteristic of new media works.

Interestingly, both, Boissier and Bourriaud include all sorts of social interactions but do not refer explicitly to transactions, though outside of the art context probably one of the most common forms of social interaction. They do not explicitly refer to transactions as a potential functionality offered or reflected via relational and interactive art.

Historically the notion of transaction appears only in the 1950 with Coarse’s reflection on the so called transaction costs, i.e. resources necessary to make a transaction happen. However, the nature of transactions has been a core interest in economics since the beginning of the discipline. They have been covered in the debates on the notion of value and especially the so called exchange value of goods. In economic terms a transaction is defined as an agreement between a buyer and a seller to exchange an asset for payment or as an economic flow that reflects the creation, transformation, exchange, transfer or elimination of economic value. The notion of value is the core entity to be exchanged and becomes often the central issue of the artwork.

Various Forms of Values

Values theories are a large part of the differences and disagreements between the various schools in economic theory. For example, the value of a commodity may be defined by factors such as labor necessary to produce it, the utility for the user, the marginal price a consumer is willing to pay for and the laws of demand and supply. In the early theories the notion of value was understood an intrinsic or objective property of an object. This objectivist school of thought was pursued by economists, such as Smith, Ricardo and Hutcheson. Only with Jevons and his interest in the utility of an object, the “subjective value” to an individual became – till today- the dominant understanding of the concept of value. The value of an object tends to be perceived as identical with its price, provided there is a market for it.

In the discourse of Cultural Economics (often informed by Philosophy) the valuation of art and non-economic goods is a major topic. According to Richard Nozick (2001) objects can have three sorts of value: intrinsic value (their unique capability to create a novel form of “unity-in-diversity”), cultural value (as symbols of a particular cultural group) and economic value (represented by someone willing to pay for them)”.Especially relevant to this context is the notion of aesthetic value, referring to the intellectual stimulation and enrichment through a work of art. Dewey argues, the value of art lays not in artwork as a mere physical object, but in the lived experience, whether this is the creative experience of the artist or appreciative experience of the audience. Similarly, Klamer defines cultural capital as “the capacity to inspire and be inspired.”

Pierre Bourdieu (1945) referred to various concepts of value as “forms of capital”. He introduced economic (financial), social (relationships) and cultural (knowledge) and later forms of capital. Later symbolic capital (status) was added. We will observe that in transactional artworks various forms of capital are simultaneously created. We will observe that transactional art thematizes the conversion of these forms of capital into each other. These “conversions” lack, of course, a clearly defined conversion rate. Instead, they may remind us of Freud’s (1960) understanding of humor as a kind of joyful play with the ambivalence of words leading to a surprising revelation of a double meaning in a joke.

Since art works are finally measured by aesthetic standards, the ultimate measure for transactional art is probably the aesthetic value they create. However, they seem to be actually judged by their degree of success of creating other values as well. As we will see, there are many examples where transactional art demonstrate a witty creation of economic value or even a business model- which is part of their success in e.g. economic terms. However, this kind of capital becomes then artistic material and subject to artistic creativity.

The Interdisciplinary Nature of Transactional Arts

Transactional art is an interesting case for the study of transdisciplinary activities: artists have to “prove” their understanding of the other domain in the sense, that they are able to craft sensible deals. This art-form inherits some of the success criteria (even though reflected and therefore often actively negated) of the discipline of business.

Art is often considered the realm of society for experiments and innovations. So, do transactional art works actually inform the other discipline, here business in a constructive way and according to its

success criteria? We argue: they actually could. We believe that artistic and business creativity have a lot more in common, than it is usually assumed. Both involve strategizing, i.e. the envisioning of goals to be pursued and the location and creation of new opportunities. But the moment an artist turns into a successful entrepreneur, he tends to disappear form the perception of the art world. And he himself, finally capable to afford a lifestyle he may have never been able to access before, may be tempted to pursue happiness solely in the economic domain.

There are artists to manage to be highly admired for their optimization of the art-production, e.g. Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst who apply the division of labor to the art production. However, if we consider these activities as production-innovations they do not seem to be transferred to other industries on a large scale. Instead it seems that the artists benefitted form the economic know-how and applied it for their own advantage.

Why are there no “art-inspired” business models? Another explanation may lie in the economic understanding of the artists: the artists do stay actually business dilettantes. According to Mary Boden (1990), creativity requires the solid penetration of the domain, especially if rule-changing creativity (potentially leading to paradigm shifts) is the measure. The dilettante transactional artist, often equipped with a deep resentment against capitalism, does actually not aim for innovative business models. Instead, he may want to convey a “critical” and anti capitalist message.

Duchamp as an Early Transactionalist

Marcel Duchamp may be considered as an early “transactionalist”. Reflecting value and a fascination for financials was a trait of Duchamp, which accompanied him throughout his production.

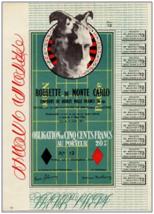

In 1919 Duchamp paid his dentist, Daniel Tzanck, a passionate art collector, with a hand drawn enlarged facsimile cheque as compensation for services rendered and as a piece of art at the same time. In 1924 he issued 30 “Monte Carlo Bonds” over 500 Francs each , and apparently raised funds from his friends in order to play Roulette at the Monte Carlo Casino promising 20% p.a. interest redeemable in three years. However, his gambling strategy did not beat the odds, but he didn’t loose either and paid only once 10% interest, one year later.

2. Marcel Duchamp, Monte Carlo Bond (No. 12) 1924

According to written records, Duchamp did never pay back the principle and, if the numbers are correct, made a profit of 13.500 Francs (initially 15.000 raised, paid back 30×50= 1.500).

In purely financial terms, the purchase of the bond for the investors may appear as a loss, but considering the deal as the acquisition of an original Duchamp artifact (that even earned a 10 % return) it may be construed as a great buy. As with his ready-mades, the accomplished artist Marcel Duchamp creates value by an act of declaration – here in the form of an amicable deal (a contract represented by an artistically designed and signed bond certificate) with his audience, i.e. collectors.

This deal is actually crafted along a variety of interpretations of the notion of value: that of Duchamp’s conceptual and artistic work in creating the bond, the value of an “original” Duchamp art piece for a collector and on the art-market, the aesthetic value of the pleasures of being inspired (open also to non-possessors) and the price or face value for which the bond is sold. The complexity of this transactional art object is derived from the interplay of the various forms of capital. Interaction becomes transaction manifested as a financial instrument, issued and authorized by a self-empowered artist who actually benefited financially. Self empowered, since the privilege of issuing of financial instruments is normally reserved for organizations within a highly regulated domain in an economy.

Artworks with a transactional component tend to challenge a fundamental western aesthetic conception demanding art to be entirely separate from the economic sphere. Thus was Duchamp repeatedly accused of lacking detachment from material concerns, though he appeared to be mainly interested in the speculative and provocative aspects of his works. Does transactional art automatically violate the principle of the autonomy of art? If art today can reflect any subject and strategy of any context in society, then why not the economic transactions which ubiquitously surround us?

Kant requires the aesthetic judgment to be “disinterested” and art should also not serve any external means, it is considered a means in itself. Therefore an art form which allows generating profits and is based on all sorts of incentives seems to be profoundly violating the postulates of this aesthetic tradition. Many interactive artworks and certainly transactional arts involve aspects of intentionality, desire and will. And as we saw in the Duchamp examples they may even involve some kind of deal-making. If one assumes with classical economics a “rational agent”, they appeal to the rationality of a somewhat motivated agent pursuing his goals.

However the strict postulates of disinterestedness and the autonomy of art as demanded by Kant, Schopenhauer and others have been weakened over time. Nietzsche mocks strongly the disinterestedness as the “philosopher’s prudishness”. Pragmatists like Dewey rejected Kant’s approach and state that artworks serve a variety of functions, such as entertainment, edification, religious inspiration, decoration, personal and social expression.

For transactional art we may argue, there is always potentially the aesthetic value, which the recipient may gain, therefore even transactional art does not – theoretically – have to violate the prerequisites of being judged as “beautiful”. Similarly to conceptual art, however, the beauty of transactional art may lie more in the inspirational value than in its’ material implementations.

Forms of Transactional Art

Denial of Profits – Economies of Dissipation

In many cases where a transaction happens between artist and audience, the artist deliberately wastes or destroys a potential gain. Thereby he apparently contradicts the central premise of modern economics assuming a “rational agent” pursuing maximal profit (this assumption has extensively been questioned within the economic discourse). These works may be interpreted in the context of an economy of dissipation in the sense of Georges Bataille (1946), who states, that the accursed share is an excessive and non-recuperable part of any economy, to be spent in either in the arts or non-procreative sexuality in order to prevent catastrophic outpourings in war.

In 1958 Yves Klein sold void space in Paris for gold, which he threw afterwards into the river Seine. Fifty years later Zoe Sheehan Saldana breeds plants as an online performance and gives them away at the end of the project. In the 70ties happenings provided all sorts of amenities to the audience. In the light of today’s “attention economy” where perception is valued in the currency of “eye-balls”, these kinds of deals may appear less one-sided.

3. Yves Klein, Void, around 1958

Internet culture and economy are highly influenced by the idea of the give-away: free software, the open source-movement, Wikipedia and most Web 2.0 characteristics rely on an economy in which sharing and giving are expected as a default attitude. If one may want to refer to these interactions as transactions which are often driven by idealistic motivations, then the payments seem to be based on primary non-monetary rewards. Of course, the idea of a free sample as a vehicle leading to further transactions is a well established sales strategy widely applied in the digital economy.

Bridging Various Arenas of Exchange

Creating counter-economies which are more or less entrenched with the real world is a strategy only few artists have the resources to do. The Dutch artist group Atelier van Lieshout designed for their utopian state-like territory in Rotterdam a currency called AvLs, which are convertible at an exchange rate of 1:1 into beer.

Entrenched with the outside world are also many economies which emerged around virtual worlds and multi user online games economies. For example, here not only players and virtual artifacts can be traded, but also the off shoring of labor intense activities to low wage countries is facilitated.

Accounting – Financial Diaries

Artists like Danica Phelps reflect their personal life in the form of a diary on daily transactions. The transactions stand for “emotional exchanges” in analogy to an accounting book keeping record of the in and out flows of cash.

Burak Arikan discloses in the online project MyPocket his personal financial records to the world in order to predict his future spending. After a predicted transaction happens, its receipt is marked with a green stamp, which shows the probability of the prediction.

Value Creation through Labor

Karl Heinz Jeron in his piece Will Work for Food creates small robots, which are sent to the audience in exchange for food sent to the artist. The robots can be “rented” for food and have the ability to draw and whistle. Since the robots are not the consumers of the food therefore the installation seems to subsidize the artist himself. The recipient provides food and the artist sends him a robot in return, which performs an audio visual artwork, an aesthetic product, which can be kept.

Mimicry of Organizational Structures and Financing Models

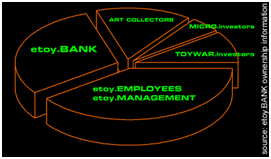

Many artists especially media artists have actually applied business practices. The art groups Etoy and RTMark not only mimic the organizational structure, appearance and rhetoric of multinational corporations, they also issue stocks and/or mutual funds in order to allow the audience to support their activities. Interesting enough, these groups use capitalistic financing techniques in order to realize critical artworks with an anti-capitalistic flair. The transactions involved may be seen as some sort of commissioning or sponsoring which has become part of the artwork itself.

Figure 3: Etoy company overview and Etoy shares, since 1995 and RT Mark, since 1998

Distribution – Shops, Buying and Selling as Artistic Expression

In transactional arts buying and selling may become means of artistic expression. Christine Hill has chosen the form of a shop for her installation “Volksboutique” in which she initially sold objects. During her “Ebayaday” performance curated artists could sell their work.

The creation of social capital and a way to overcome certain mechanisms of social exclusion provides the Spanish art group “Mejor Vida”. All sorts of subversive goods and services, “items for a better life”, can be ordered through this online shop: fake subway tickets, student ID cards stamps “as well as printable barcode stickers supposed to lower prices”.

Figure 2: Mejor Vida Corp, 2002

So called “auction artists” (Atkins, online) use existing market platforms such as Ebay for highly conceptual artworks to auction off e.g. their time and availability (Carey Peppermint), private data (Jeff Gates), or their “body, with minor imperfections” (Michael Daines). Often artists experience no demand for these offers at all. Suggesting potential transactions becomes the artwork, even if these transactions actually never happen.

Online Customization, Commissioning and Mash-ups as Value Chains

The economic principle of division of labor has become the artistic attitude for artists like Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons and Mark Kostabi who outsource parts of the creative production. In media art it online commissioning may be viewed as an extension to this trend.

A.Koblin initiated with the project The Sheep Market a collection of 1000 sheep created by workers on a online work platform. Each worker was paid 0.02 US$ to “draw a sheep facing left”. The artist then offered these drawings as “lickable stamps” for 20$ each to be ordered via the website. In Ten Thousand Cents he

and T. Kawashima let the online workforce create a digital representation of a $100 bill. Thousands of individuals painted a small part of the bill without knowledge of the overall task.

Figure 4: Aaron Koblin, Takashi Kawashima, Ten Thousand Cents, 2008

Related to his auction art are Carey Peppermint’s online commissioning activities, where he

allows the EBay audience to conceptualize an artwork. In the tradition of conceptual art he will then execute these tasks and document them. IP rights are shared between him and the commissioner.

The art-group We Make Money and Not Art uses Google ads to generate revenue from the hits on their website. For the digital activism project Google Will Eat It Self the group Uebermorgen designed a value chain as a closed circuit of transactions: they first generated profits by manipulating the Google ad-sense program and used these funds to buy stocks of Google.

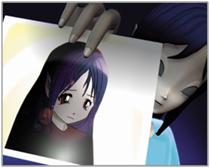

Another way of a business mesh-up and a new way of reflecting Intellectual Property licensing and the re-use of creative products is work by Philippe Parreno. He acquired the rights (for 500 Franc) of a digital Japanese manga character called Annelee from an animation company, revamps the design and then allows other artists to use it for their work, i.e. create artworks with it.

Figure 5: Philippe Parreno, Anywhere Out of the World, 2000

Facilitating the Exchange of Values – The Market as Meta Art

A. Galloway states that today’s internet protocols are “synonymous with possibility” and that the internet facilitates the economic form of market places. Media art has always been the creation, design, structuring and control of possibility spaces (the set of choices offered by non-linear media) and artists have attempted to continuously expand these. One transactional artistic strategy is the creation of market places itself. The artist may not participate in any transaction, but merely provide the platform for potential transactions.

Without an explicitly artistic intention Robin Hanson created Idea Futures a market platform to bet on opinions. He considered this online market a potential tool for collective decision making and won the Prix Ars Electronica Price 1995 for this work.

The art foundation Mediamatic hosts a matchmaking service facilitating, e.g. encounters with Russian Brides. This marketplace is meant as a contribution to the discourse around foreign workers in the Netherlands and a critical reflection of the respective immigration policies. “Is it an art project? Yes. You’re at Mediamatic.” they define the status of the marketplace on their website.

For 2009/10 Mediamatic plans to launch a “travel-network for creative professionals” which allows hiring “guides” for 45 EUR from the creative community when travelling to other cities.

Mediamatic Russian Brides, 2008

Christin Lahr initiates a market for the exchange of personal data as a critical work on privacy issues in the internet. With SellBack she allows the audience to evaluate their privacy data and then offer these data on her market platform.

Figure 6: Don’t Pay Back, Sellback, Enter the World Wide Data Trade, Christin Lahr, 2006

The project Open-Clothes.com envisions a platform for all transactions and interactions around the design and distribution of customizable clothes and won also an Ars Electronica distinction award for communities in 2004.

For these artistic online markets the principles of web 2.0 internet economy seem to apply. As the ideal media to match niche demand and niche supply (according Chris Anderson’s (2006) Long Tail assumption) these markets become niche products themselves, often defying their lack of liquidity. Collages of transactional modules may be meshed-up in this art form, similarly to the value chains of online businesses.

An actually functioning real time market running over years have the art group Derivart installed in the centre of Barcelona. They founded the Bar Bolsa, a pub in which the prices for alcoholic drinks fluctuate according to demand.

Figure 7: Bar La Bolsa, Barcelona, since 1997

Reflecting the Meta-Business of Finance

Finance is considered the “brain of an economy” and as a service sector facilitates the allocation of capital and the mitigation of risks within a society (and/or the global economy). The mechanisms of risk and reward, investing and speculation have interested artists such as Duchamp, as we saw earlier. However, this field may have more potential, than currently explored by artists.

An attempt to speculate with funds from the cultural sector was undertaken by American artist Robert Morris in 1969 (Siegel, Mattick, 2004). He proposed that the Whitney museum provide a small amount of money to invest in what he called blue “chip art” works which he was proposing to sell in Europe at higher prices and thereby profit the museum. The museum’s trustees however considered this idea as too risky. They made Morris to invest in “risk-free” assets, such as Treasury Bonds, which in the financial world are the benchmark for lowest/no risk. The artwork consists of the correspondence Morris and the trustees and discussed refers to notions of risk.

Relying on his expertise as a non-professional stock trader, artist Michael Goldberg played the stock market for three weeks from a gallery generating charts and other forms of data visualization as output. He had built a form of “strategic interface” to the online market in the form of a tower. Goldberg had raised 50.000 AU$ from befriended investors, traded without personal risk and closed with a 1000 AU$ loss.

Creative Deal-Making

Though many transactional artworks seem to rely on some sort of agreement, not many artists address them openly. Christin Lahr instead, makes agreements and contracts the explicit subject of her works. In the German project Nichts Zu Verschenken (Nothing to Give Away) she offers the audience to sign a gift contract about “Nothing”. This contract can later be sold like any artwork and a profit can be made. If the audience does not sign, they also have “Nothing”, but they do not have the right to benefit from the appreciation in value – the artist claims.

Conclusion – Principles of Transactional Arts

Many interactive art works make use of interactive media in a transactional way and transfer values. The artists take seldom profit and in case of financial gains they are often deliberately given away. This may be part of the aesthetic heritage to 18th century aesthetics and the requirement of the disinterestedness of the aesthetic judgment.

The transactions involve various forms of capital, e.g. cultural, social, economic and symbolic capital. The aesthetic success of a transactional artwork seems not to depend on a successful transaction. So, even in the cases of unanswered auction art offers and illiquid markets – one may argue in favor of transactional art – their aesthetic value as a form of cultural capital is not diminished.

Artists using interactive media design possibility spaces. Artists using transactional media work additionally with incentives. As governments steer the behavior of their citizens e.g. with tax incentives, artists now facilitate and/or execute transactions as part of their work. They craft deals and foster the exchange of values. Sometimes they design decision architectures where they may “nudge” participants into desired behaviors.

The social positioning of agents involved plays an important role in transactional art. Their actual negotiation power becomes a constituent of the artwork. Therefore transactional artworks are always “aspectual” and relative to the social positions of the agents involved. The characteristic of variability of interactive media and transactional media may haul this kind of art.

Artists reflect their negotiation power in various ways, often with an audacious gesture of self-empowerment. The artist often creatively circumvents the limitations of his actual social position and lack of economic capital by claiming the possession or creation of fictitious values. As demonstrated by Duchamp non financial value were successfully exchanged for other forms of capital and generated, besides the artistic merits, financial profits for the artist.

Often transactional artists provide a meta-platform for others to post their offers and demands or even design incentive-structures .In this sense, transactional art leads often to meta-art works enabling creations by others in general and/or artists in particular.

Since many transactional artworks involve deal-making, an element of rationality is characteristic for the interactions taking place. Whoever the counterparty is, she has to accept the offer preceding the transaction. Therefore transactional art involves a kind of agreement or contract which may be implicitly or explicitly stated. The core function of contracts is to organize the transfer of values; therefore it is not surprising that transactional artist actually reflect this kind of social agreement. The proposed deals have to appeal to the value systems and rationality of the participants, even if they come from different social contexts. This may be seen as a refreshing alternative to the proven artistic strategies of the dysfunctional and absurd.

As a highly interdisciplinary art form, transactional art offers insights in how disciplines may inform each other and how interdisciplinary works are actually judged by the contributions they make to all disciplines involved and to what extent they fulfill the success-criteria in the different domains, here the art and business world.

Many of the transactional artworks we saw spell out a radical critique of capitalistic principles. With the development of the internet as a transactional medium and its reflection by artists there may be future potential for more constructive explorations of social interactions in general and capitalism in particular. Transactional art may be highly demanding to its participants but – since always situated within the contexts of economic resources and spheres of power – could reward society with some valuable insights.

References

C. Anderson, The Long Tail, Random House Business Books, 2006

B. Arikan, http://burak-arikan.com/

R. Atkins, Art as Auction, http://www.mediachannel.org/arts/perspectives/auction/index.shtml

G. Bataille, La Part Maudite, 1946 and 1949, translated, The Accursed Share, 1991

Beauty Exhibition, http://www.tav.org.sg/Archives_Chrono.htm

H. Bernhard,. Media Hacking Digitaler Aktionismus., http://www.ubermorgen.com/publications/iem_cube_2005/CubeMediaHacking.htm

J-L. Boissier La relation comme forme – Figuere de la interactivite, Genève Musee’e d’Art Moderne et Contemporain, 2004 and http://www.ciren.org/ciren/productions/livre/index.html

P. Bourdieu, The Forms of Capital: English version in J.G. Richardson’s Handbook for Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, 1986, pp. 241–258.

N. Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, Le Press Du Reel, 1998, 2002 (English translation) p 112.

C.Crawford, What exactly is Interactivity? The Art of Interactive Design, No Starch Press, 2002. p.3-12.

M. Boden, The Creative Mind: myths and mechanisms. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. 1990

Derivart, http://www.derivart.info

Atelier Van Lieshout, http://www.ateliervanlieshout.com,

Etoy http://www.etoy.com/fundamentals/

S. Freud, Jokes and their Relation to the Subconscious, Norton Library, NY, 1960. p36

P. Galloway, Protoco: How Control Exists after Decentralization, Leonardo Book l, MIT Press, 2004, p. 227.

M. Goldberg, Intervention Art, http://www.michael-goldberg.com, catchingafallingknife.com

R. Hanson, Idea Futures, http://hanson.gmu.edu/ideafutures.html

M. Hutter, Value and Valuation of Art, in: Handbooks of Economics of Art and Culture, Vol 1, ed. by V. Ginsburgh, D. Throsby,p 183

D. Judovitz, Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit, University of California Press , 1998.

A. Klamer in Handbook of Economics and Culture, Vol 1, p 465-7.

J. Kosuth, Unpublished Notes 1970, in: Art in Theory 1900 – 2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Wiley-Blackwell; 2002

C. Lahr, Don’t Pay Back – Sell Back, http://www.sellback.net,

C. Maby, Mind Art, www.mind-art.fr,

L. Manovich, The Language of New Media, Leonardo Book, MIT Press, 2001

Mejor Vida Corp, 2002, http://www.irational.org/mvc/english.html),

R.T. Mark, RTMark: Your Real Corporation Clearinghouse, http://www.rtmark.com,

S. Mc Millan, Exploring Models of Interactivity from Multiple Research Traditions: Users, Documents, and Systems in Handbook of New Media, 2002.

Mediamatic, Russian Bride, www.mediamatic.net/russianbrides,

Mediamatic, Travelnet, http://travel.mediamatic.net/

R. Nozick, Invariances, Belknap Press, Cambridge, MA, 2001

P. Parreno, http://www.stretcher.org/archives/r3_a/2003_02_10_r3_archive.php,

D. A. Plewe, Transactional Art, Proceeding of the 16th ACM international conference on Multimedia. 2008, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada October 26 – 31, 2008 p 977-980.

M. Porter, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, Free Press, 1985

Z. S. Saldana, http://www.zoesheehan.com,

J. Stahl,. Kunst als Giveaway, http://www.uni-bonn.de/~uph60016/texte/givestahl.htm

K. Siegel, Paul Mattick. Money- Artworks, Thames and Hudson, London, 2004.

D.Tapscott, Wikinomics, How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything, Penguin Group, New York, 2006

Uebermorgen, GWEI, Google Will Eat Itself, http://gwei.org/pages/texts/media_hacking.html

We-Make-Money-Not-Art, http://www.we-make-money-not- art.com/archives/cat_ars_electronica.php

Transactional Art

October 23, 2009

Daniela Alina Plewe

Transactional Arts – Art about Business

Keywords: Interactive Art, Media Art, Transactional Art, Business

Abstract

Interactive media, especially the internet, are often used in an economic context where interactions are actually transactions. We focus on artists who apply economic principles and coin those works as “transactional arts”. We will observe that many accomplished new media works actually have transactional features and that the characteristics of the internet economy seem to facilitate this kind of art form.

In the field of transactional arts, buying and selling are means of self-expression, marketplaces are created as a form of art, mesh-ups may resemble online businesses and most importantly, incentives become artistic material. Often a kind of deal-making is involved and transactional art works therefore appeal to some sort of rationality.

Transactional artists actually apply economic know-how and therefore create not only aesthetic value but also economic capital. They therefore tend to fulfill success criteria of both disciplines involved – here art and business.

Transactional Art

We will concentrate on art, where a transaction is explicitly part of the work. With the following overview of transactional art we will not only introduce works” which make money” but any kind of art where some sort of value is explicitly exchanged. Often these values are financially viable.

The art-scene and the business world are two fields of society which tend to be not very intertwined. Of course there are all sorts of businesses with art, i.e. the art business and the art market where the two domains touch each other. However, we will not refer to the commercial activities related to the art market. Under the notion of transactional art we will also not address to the body of artworks, which reflects economic concepts in a broader sense, e.g. painting of money, sculptures in gold etc.

The Transactional Component – from Interaction to Transaction

A basic form of interaction may be defined as a kind of cybernetic loop in which two agents (human or systems) reciprocally listen, speak and think (Crawford 2002). This simplistic concept of interaction based on the sender-recipient model corresponds with the understanding of a cybernetic loop. We will use the cybernetic nature of both an interaction and a transaction to draw a parallelism between the two.

1.Interaction and Transaction

In the field of transactional art we will observe a variety of combinations of these constituents.. Agents may vary: in the artistic context the transactions can involve as agents the artist, the audience, but possibly also subcontractors or contingent market-participants. The settings of the transactions may also be different. Some may take place within the art world, others involve the commercial domain and some artists even create their own marketplaces. In this sense transactional arts stand in the tradition of art-forms taking place in the social sphere, often involving all sorts of collaborations.

There is a variety of approaches to interactivity, which all seem compatible with the above over all structure. For example, Sally Mc Millian (2002) refines this scheme and differentiates between user-to-user, user-to-document (static information) and user-to-system (involving a strong algorithmic component) interactivity and defines then the relative position of freedom and control between human and machine agents.

The notion of interactivity has also been reflected in the field of aesthetics, especially in the context of interactive art. Nicolas Bourriaud (2002, p 112) introduces the concept of relational aesthetics as a “set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space.” He emphasizes the human-to-human aspect and refers to artworks, which explicitly create social events.

In his explorations on the aesthetics of interactive art, Jean-Luc Boissier (2002, online) considers relations (and relationships) as its genuine determinants. Despite the openness of interactive art, “to all sorts of particular states” this genre of art is “uniquely determined by the functionalities it offers”. The particular states one may interpret as possibility spaces, i.e. a feature of non-linear media referring to the sum of all variations and states of the technical system in which the artwork may appear. Manovich (2001) addressed this idea with the concept of “variability” as a genuine characteristic of new media works.

Interestingly, both, Boissier and Bourriaud include all sorts of social interactions but do not refer explicitly to transactions, though outside of the art context probably one of the dominant forms of social interaction. They do not explicitly refer to transactions as a potential functionality offered or reflected via relational and interactive art.

Historically the notion of transaction appears only in the 1950 with Coarse’s reflection on the so called transaction costs, i.e. resources necessary to make a transaction happen. However, the issues of transacting have been a core interest in economics since the beginning of the discipline. They have been covered in the debates on the notion of value and especially the so called exchange value of goods. In economic terms a transaction is defined as an agreement between a buyer and a seller to exchange an asset for payment or as an economic flow that reflects the creation, transformation, exchange, transfer or elimination of economic value. The notion of value is the core entity to be exchanged and becomes often the central issue of the artwork.

Various Forms of Values

Values theories are a large part of the differences and disagreements between the various schools in economic theory. For example, the value of a commodity may be defined by factors such as labor necessary to produce it, the utility for the user, the marginal price a consumer is willing to pay for and the laws of demand and supply. In the early theories the notion of value was understood an intrinsic or objective property of an object. This objectivist school of thought was pursued by economists, such as Smith, Ricardo and Hutcheson. Only with Jevons and his interest in the utility of an object, the “subjective value” to an individual became – till today- the dominant understanding of the concept of value. The value of an object tends to be perceived as identical with its price, provided there is a market for it.

In the discourse of Cultural Economics (often informed by Philosophy) the valuation of art and non-economic goods is a major topic. According to Richard Nozick (2001) objects can have three sorts of value: intrinsic value (their unique capability to create a novel form of “unity-in-diversity”), cultural value (as symbols of a particular cultural group) and economic value (represented by someone willing to pay for them)”.Especially relevant to this context is the notion of aesthetic value, referring to the intellectual stimulation and enrichment through a work of art. Dewey argues, the value of art lays not in artwork as a mere physical object, but in the lived experience, whether this is the creative experience of the artist or appreciative experience of the audience. Similarly, Klamer defines cultural capital as “the capacity to inspire and be inspired”

Pierre Bourdieu (1945) referred to various concepts of value as “forms of capital”. He introduced economic (financial), social (relationships) and cultural (knowledge) and later forms of capital. Later symbolic capital (status) was added. We will observe that in transactional artworks various forms of capital are simultaneously created. We will observe that transactional art thematizes the conversion of these forms of capital into each other. These “conversions” lack, of course, a clearly defined conversion rate. Instead, they may remind us of Freud’s (1960) understanding of humor as a kind of joyful play with the ambivalence of words leading to a surprising revelation of a double meaning in a joke.

Since art works are finally measured by aesthetic standards, the ultimate measure for transactional art is probably the aesthetic value they create. However, they seem to be actually judged by their degree of success of creating other values as well. As we will see, there are many examples where transactional art demonstrate a witty creation of economic value or even a business model- which is part of their success in e.g. economic terms. However, this kind of capital becomes then artistic material and subject to artistic creativity.

The Interdisciplinary Nature of Transactional Arts

Transactional art is an interesting case for the study of transdisciplinary activities: artists have to “prove” their understanding of the other domain in the sense, that they are able to craft sensible deals. This art-form inherits some of the success criteria (even though reflected and therefore often actively negated) of the discipline of business.

Art is often considered the realm of society for experiments and innovations. So, do transactional art works actually inform the other discipline, here business in a constructive way and according to its success criteria? We argue: they actually could. We believe that artistic and business creativity have a lot more in common, than it is usually assumed. Both involve strategizing, i.e. the envisioning of goals to be pursued and the location and creation of new opportunities. But the moment an artist turns into a successful entrepreneur, he tends to disappear form the perception of the art world. And he himself, finally capable to afford a lifestyle he may have never been able to access before, may be tempted to pursue happiness solely in the economic domain.

There are artists to manage to be highly admired for their optimization of the art-production, e.g. Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst who apply the division of labor to the art production. However, if we consider these activities as production-innovations they do not seem to be transferred to other industries on a large scale. Instead it seems that the artists benefitted form the economic know-how and applied it for their own advantage.

Why are there no “art-inspired” business models? Another explanation may lie in the economic understanding of the artists: the artists do stay actually business dilettantes. According to Mary Boden (1990), creativity requires the solid penetration of the domain, especially if rule-changing creativity (potentially leading to paradigm shifts) is the measure. The dilettante transactional artist, often equipped with a deep resentment against capitalism, does actually not aim for innovative business models. Instead, he may want to convey a “critical” and anti capitalist message.

Duchamp as an Early Transactionalist

Marcel Duchamp may be considered as an early “transactionalist”. Reflecting value and a fascination for financials was a trait of Duchamp, which accompanied him throughout his production.

In 1919 Duchamp paid his dentist, Daniel Tzanck, a passionate art collector, with a hand drawn enlarged facsimile cheque as compensation for services rendered and as a piece of art at the same time. In 1924 he issued 30 “Monte Carlo Bonds” over 500 Francs each , and apparently raised funds from his friends in order to play Roulette at the Monte Carlo Casino promising 20% p.a. interest redeemable in three years. However, his gambling strategy did not beat the odds, but he didn’t loose either and paid only once 10% interest, one year later.

2. Marcel Duchamp, Monte Carlo Bond (No. 12) 1924

According to written records, Duchamp did never pay back the principle and, if the numbers are correct, made a profit of 13.500 Francs (initially 15.000 raised, paid back 30×50= 1.500).

In purely financial terms, the purchase of the bond for the investors may appear as a loss, but considering the deal as the acquisition of an original Duchamp artifact (that even earned a 10 % return) it may be construed as a great buy. As with his ready-mades, the accomplished artist Marcel Duchamp creates value by an act of declaration – here in the form of an amicable deal (a contract represented by an artistically designed and signed bond certificate) with his audience, i.e. collectors.

This deal is actually crafted along a variety of interpretations of the notion of value: that of Duchamp’s conceptual and artistic work in creating the bond, the value of an “original” Duchamp art piece for a collector and on the art-market, the aesthetic value of the pleasures of being inspired (open also to non-possessors) and the price or face value for which the bond is sold. The complexity of this transactional art object is derived from the interplay of the various forms of capital. Interaction becomes transaction manifested as a financial instrument, issued and authorized by a self-empowered artist who actually benefited financially. Self empowered, since the privilege of issuing of financial instruments is normally reserved for organizations within a highly regulated domain in an economy.

Artworks with a transactional component tend to challenge a fundamental western aesthetic conception demanding art to be entirely separate from the economic sphere. Thus was Duchamp repeatedly accused of lacking detachment from material concerns, though he appeared to be mainly interested in the speculative and provocative aspects of his works. Does transactional art automatically violate the principle of the autonomy of art? If art today can reflect any subject and strategy of any context in society, then why not the economic transactions which ubiquitously surround us?

Kant requires the aesthetic judgment to be “disinterested” and art should also not serve any external means, it is considered a means in itself. Therefore an art form which allows generating profits and is based on all sorts of incentives seems to be profoundly violating the postulates of this aesthetic tradition. Many interactive artworks and certainly transactional arts involve aspects of intentionality, desire and will. And as we saw in the Duchamp examples they may even involve some kind of deal-making. If one assumes with classical economics a “rational agent”, they appeal to the rationality of a somewhat motivated agent pursuing his goals.

However the strict postulates of disinterestedness and the autonomy of art as demanded by Kant, Schopenhauer and others have been weakened over time. Nietzsche mocks strongly the disinterestedness as the “philosopher’s prudishness”. Pragmatists like Dewey rejected Kant’s approach and state that artworks serve a variety of functions, such as entertainment, edification, religious inspiration, decoration, personal and social expression.

For transactional art we may argue, there is always potentially the aesthetic value, which the recipient may gain, therefore even transactional art does not – theoretically – have to violate the prerequisites of being judged as “beautiful”. Similarly to conceptual art, however, the beauty of transactional art may lie more in the inspirational value than in its’ implementation.

Forms of Transactional Art

Art as a Give Away and Denial of Profits

Often artists act in opposition to economic principles e.g. the artists generate some values but give them away or deny taking the profit. Often this is a deliberate choice in opposition to economic principles and a critique of capitalism. The idea to discard profits may be motivated to the principles of 18th century aesthetics as discussed above.

Especially when a transaction happens between artist and audience, artists seem to waste potential gains thereby apparently contradicting the central premise of modern economics assuming a “rational agent” pursuing maximal profit. The notion of the rational agent though has been heavily criticized within the economic disciplines in the meantime, such as in behavioral economics and behavioral finance.

A famous example of non profitable transaction is Yves Klein’s work “Void” from 1958. Klein managed to sell void space in Paris for gold, which he afterwards threw into the river Seine. As if selling void is an illegitimate activity, the profit has to be wasted afterwards “in order to restore the “natural order” that he had unbalanced by selling the empty space.

3. Yves Klein, Void, around 1958

Economy of Dissipation

Art as a give-away may interpreted in the context of George Bataille’s (1946) theory of consumption, where he states in the introduction that “that the extension of economic growth itself requires the overturning of economic principles—the overturning of the ethics that grounds them.”The “accursed share is an excessive and non-recuperable part of any economy which is destined to one of two modes of economic and social expenditure: it must either be spent luxuriously and knowingly without gain in the arts, in non-procreative sexuality, in spectacles and sumptuous monuments, or it is obliviously destined to an outrageous and catastrophic outpouring in war.”

There are many artworks, where the artist is actually giving for free some entity of value to the audience. According to Johannes Stahl, Plinius, the younger, refers to the painter Zeuxis, who was so convinced about the quality of his art that he considered any price for it as too low and therefore he would have to give away his art as a present. Another example is the Trojan horse, argues Johannes Stahl – art as a gift with strings attached.

Handling out gifts through the internet is an approach by contemporary artist Zoe Sheehan Saldana chooses. She breeds plants as an” online performance” monitored by cameras in real-time and gives them away at the end of the project. She uses the medium internet in order to distribute her presents.

4. Zoe Sheehan Saldana, Homegrown, 2007

In the light of an “attention economy” where perception is valued in the currency of “eye-balls”, these kinds of deals may appear less one-sided. We are today used to think of attention as a value, which e.g. advertisers are willing to pay for in an eye-ball economy.

Internet culture and economy are highly influenced by the idea of the give-away: free software, the open source-movement, Wikipedia and most Web 2.0 characteristics rely on an economy in which sharing and giving are expected as a default attitude. If one may refer to these interactions as transactions which are often driven by idealistic motivations, then the payments seem to be based on primary non-monetary rewards.

Blending with Real Economies

Creating counter-economies which are more or less entrenched with the real world is a strategy only few artists have the resources to do. The Dutch artist group Atelier van Lieshout designed for their utopian state-like territory in Rotterdam a currency called “AvL”s, which are convertible at an exchange rate of 1:1 into beer.

5. Atelier van Lieshout, 100 AvL, 2003

Entrenched with the real world are also many economies which Blending with Real Economies

Creating counter-economies which are more or less entrenched with the real world is a strategy only few artists have the resources to do. Personal Finances and Financial Diaries

This kind of artistic work reflects financial accounting as a structure of personal life, often thereby reflecting a perspective of financial planning. Often inspired by an autobiographic note, these works may creatively reflect the artist’s suffering from a lack of financial resources.

Financial Diaries

A work, where personal finances are the centre of attention is MyPocket by Burak Arikan in 2007. He discloses his personal financial records to the world in order to predict his future spending. “It (the software) explores and reveals essential patterns in the daily transactions of my bank account and discloses my personal finances to the world.” He then calculates the probability of new transactions and generates a visualization of his spending patterns. This work reflects financial accounting as a structure of personal life documenting real life transactions.

6. Burak Arikan, My Pocket, 2007

Danica Phelps documents her personal transactions since 1996. “She notes her financial transactions in dollars, red for expenses, green for income and grey for credit. She not only uses these accounts as a form of diary, but associates objects and drawings around them. The transactions stand for “emotional exchanges” in analogy to an accounting book keeping record of the in and out flows of cash.

Art Implementing Business Practices

As the core of transacitonal art we consider artworks, which actually apply business practices. This kind of artwork ranges from all sorts of organisational mimicry and declarations of value to new forms of business models. The latter we find especially interesting, as they seem fullfill not only aesthetic, but also economic criteria. Many of these artworks use the internet to allow for transactions of money and rely on it as a transactional medium.

Organisational and Financial Business Structures

The art groups Etoy and RTMark not only mimic the organizational structure, appearance and rhetoric of multi national corporations, they also issue stocks and/or mutual funds in order to allow the audience to support their activities.

The members of Etoy designed their unique “corporate identity” including graphic designs, uniforms, temporary architecture etc. They managed to create a subversive, “pseudo-corporate” atmosphere and issued stocks as a private company. These stocks have later been “materialized” into tangible products, such as brass plates, in order to cater to the demands of an object oriented art market.

7. Etoy shares, 1995 onwards

The so-called Toywar (1999) was a famous dispute about the domain name leading to one of the first massive internet mobilizations in favor of an activist group versus a publicly listed multi national corporation; the internet toy retailer Etoy.Inc. The battle over similar domain names and the accusation of trademark dilution (among others) led to a lawsuit with an injunction to close the activist’s website. However, the corporation soon dropped the lawsuit and the artist website went back to operation.

According to “Etoy’s Corporation’s” their mobilization incurred the loss of $4.5 billion dollars in market capitalization; Therefore the “performance” has been coined as the “most expensive in art history”. This monocausal explanation may be part of an overstatement by the art group, however, it is one of the first cases where the power of internet-based mouth to mouth communication was demonstrated and massively damaged the stock value of a publicly listed company. Communication in the interactive media internet affected “real” financial values. Internet activism discovered the transactional power of their medium.

Another activist group is RTMark brings together activist projects and potential investors (the name is derived from “Registered Trademark”). Users may post projects, such as the “Barbie Liberation Organization”, in which the voice-boxes of talking Barbie and GI Joe toys were swapped, and the toys then returned to the store (1993). In the project “VoteAuction” United States citizens were offered the ability to sell their presidential vote to the highest bidder during the 2000 US presidential election. The website was later moved to the art-group Ubermorgen in Austria since various US States sued the site for alleged illegal vote trading.

RTMark explicitly refers to financial concepts, such as “investing”, “mutual funds”, risk management” etc.. They thereby ask the question of the value and “return of investment” more directly than Etoy. As they state on their FAQ section of the website, their aim is “cultural profit, not financial”

8. RT Mark, 1998 onwards

Interesting enough, these activist groups use capitalistic financing techniques in order to realize critical artworks with an anti-capitalistic flair. The transactions involve a sympathetic audience who is offered the chance to contribute and/or invest as some sort of commissioning or sponsoring. Anticipating and facilitating these interactions and transactions via the RT mark corporation as a brokerage has become an artwork itself. The interactive medium internet is used as a transactional medium in this kind of work.

The value creation via management consulting was explored by artists like Carey Young and Christina Jankowski. Carey Young offers conflict resolution services on the street as a kind of performance in the public space. Christian Jankowski lets a strategic management consultant analyze a gallery and its next door shop and displays the analysis via a video installation.

The economic principle of division of labor has become the artistic attitude for artists like Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons and Mark Kostabi who outsource parts of the creative production. Sol Le Witt, the protagonist of conceptual art “outsourced” the implementation of his artworks via verbal instructions.

9. Santiago Sierra, 8 Foot Line Tattooed on Six Re-numerated People, 1999

Santiago Serra, by paying drug addicts in their preferred drugs to perform his art by getting tattooed a line on their back, become the employer and – the exploiter in Marx terms. We consider this controversy work as transactional as it is a relationship between the artist and some sort of subcontractor.

Shops, Buying and Selling as Artistic Expression

These kinds of artworks choose the form of a shop or other ways to buy or sell something. In transactional arts buying and selling may become means of artistic expression. Often artists experience no demand for these offers at all. Suggesting potential transactions become the artwork, even if these transactions never actually happen. Installation art in the form of shops has been extensively explore by artists like Christine Hill with her “Volksboutique” installations, which only in the very beginning allowed the audience to actually purchase the items.

“Items for a better life” offers the Spanish art group “Mejor Vida”. All sorts of subversive goods and services, such as fake subway tickets, student ID cards etc. can be ordered through this online shop. Some of these products challenge social mechanisms of exclusion and institutional barriers. The buyers may acquire some sort of what Pierre Bourdieu (1946) would have called social capital, i.e. value that emerges through relationships an individual has access to.

10. Mejor Vida Corp, 2002

Auction Art

Auction artists” use existing market platforms such as eBay for highly conceptual artworks to auction off some sort offer. Thereby they may reach other audiences than the usual art recipients.

Carey Peppermint allows the online audience to conceptualize an artwork, which he, in the tradition of conceptual art will then execute and document. The documentation in the form of a video tape he then sends to the commissioner, who together with the artist holds the intellectual property rights. The artist presents this being at service in a way that hardly any thing would be an impossible, though he excludes sexual and immoral requests.

Here the artist involves the audience to actually participate in the strategic part of the creation of an artwork. He manages to isolate what could be called the “strategic creativity”, the purely conceptual aspect similar to a brief for the artist. Interestingly he extends artistic creativity towards this kind of strategic brief and is considers it as a relevant contribution to the art work. Therefore he is willing to share the IP rights with his co-creators.

11. Carey Peppermint, High Bidder, 2000

Jeff Gates tries to auction off in vain his private data and shopping and TV viewing habits thereby critically referring to practices of digital customer relation ship management. He finally creates “handsome limited edition prints” of the data and manages to sell them to friends. Again, a conceptual internet artwork seems to demand some sort of materialization in order to become sellable.

In a similar piece, Michael Daines offers his own body “body, with minor imperfections”. As Peppermint he excludes sexual connotations but does offer and thematizes the economic concept of availability of the workforce.

Online Businesses, Online Customization and Mash-ups

Using the internet as a transactional medium is especially the case for this group of transactional works. Value Creation in the form of online businesses has been explored by the artist group “We make money not art”. By positioning “Google Ads” on their site they apply a common internet marketing technique and allow Google to display relevant contextual ads. The site is a kind of art news portal and blog. In case of a click and a transaction the owner of the website is rewarded with a small fee. So the artist capitalized his audience’s attention and one may argue converts aesthetic and cultural values into financial profit.

A collaborative approach for online customization has French artist Caroline Maby chosen. Under the “label mind art”, she offers her own oil paintings on a website and allows the audience to “transcend her paintings”. With a special tool users can transform her art and then send the new images back to the artist who then offers to print them out for a price which is above the “pure production price” of the print. The artist does not state how she prices her artistic “added value”.

A form of online commissioning is the work of Aaron Koblin, who posts a task on the internet and let’s the audience create a work, for which he actually pays. The Sheep Market is a collection of 1000 sheep created by workers on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Each worker was paid 0.02 US$ to “draw a sheep facing left”. The collection period took 40 days, the artist rejected more than 600 submissions and offers them as “lickable stamps” for 20$ each to be ordered via the website. In Ten Thousand Cents Koblin and Kawashima let through the online workforce create a digital representation of a $100 bill. Using a custom drawing tool, thousands of individuals painted a tiny part of the bill without knowledge of the overall task. Workers were paid one cent each via Amazon’s “Mechanical Turk” distributed labor tool.

A value chain in the sense of Michel Porter is created by the group Uebermorgen. Porter describes a value chain as a set of steps which creates product or service and basically adds value in every step. With “Google Will Eat It Self” the group designed a value chain as a closed circuit of transactions: they first generated profits by manipulating the Google ad-sense program and used the generated funds to buy stocks of Google. The illegal manipulation actually generates financially viable values. But again, the artists deny themselves to take the profit and rather reinvest the generated funds. This work was soon taken down due to the legal objections of Google.

12. GWEI, Google Will Eat Itself, 2004-2005

A new way of reflecting licensing and the re-use of intellectual property applied artist Philippe Parreno. He acquired the rights (for 500 Franc) of a digital Japanese manga character called Annelee from an animation company, revamps the design and then allows other artists to use it for their work, i.e. create artworks with it. Instead of advertising agencies or other commercial users Parreno offers this virtual character to other artists thereby creating a kind of meta-artwork.

13. Philippe Parreno, Anywhere Out of The World (2000)

Creative Deal-Making

An innovative approach to selling their art pursued the Singaporean concept art group Artist’s Village, who decided to pay collectors to collect their work (Beauty Exhibition 2002).

“Sums above 1 $$ will be offered by the artists to encourage Singaporean to keep one of their creations. The objective of the exercise are two fold: 1. Singaporeans who may never have considered collecting art before may now be spurred to do so on terms that they might be better able to appreciate, that of pecuniary benefit; 2. Singaporeans who do collect art often have conservative or unadventurous tastes, and the reversal of monetary flow might enable them to consider art of merit which need not be pretty, decorative or inoffensive.”

He the artists are actually willing to pay for the “education” of their audience (Bourdieu would call it acquisition of cultural capital) and create perhaps successfully some future demand through initial sponsoring. This meta-concept was part of the exhibition, but not featured as an artwork itself.

Differently, Christin Lahr makes contracts as their explicit subject of works. In the German project “Nichts Zu Verschenken”(“Nothing To Give Away”) she offers the audience to sign a gift contract about “Nothing”. This contract can later be sold like any artwork and a profit can be made. If the audience does not sign, they also have “Nothing”, but they do not have the right to benefit from the appreciation in value– the artist claims. The contracts are materialized as plastic foils with a cut out form, e.g. a circle[1]. Lahr plays with the various meanings of the notion of “Nichts”, which is at the same time subject of an agreement between audience and artist. Again, it is a free gift and not a financial transaction that the artist engages the audience with. .

The Market as an Art Form

Alexander Galloway (2004, 227) states that today’s internet protocols are “synonymous with possibility” and that the internet facilitates the economic form of market places. Media art has always been the creation, design, structuring and control of possibility spaces (the set of choices offered by non-linear media) and artists have attempted to continuously expand these. One transactional artistic strategy is the creation of market places themselves. The artist may not participate in any transaction, but merely provide the platform for potential transactions. In that sense they may be considered as meta-artworks using transactional media.

Without an artistic intention Robin Hanson created “Idea Futures” a market platform to bet on opinions, mostly political issues. Users could actually “put their money where their mouth is” and according to the development of events win or loose. Hanson considered this online market a potential tool for collective decision making. The jury of the Prix Ars Electronica 1995 discovered him and rewarded him with a Golden Nica. Under the name of “prediction markets” these kind of online poll systems have since then been researched in economic and political disciplines.

The art foundation Mediamatic hosts a matchmaking service facilitating, e.g. encounters with “Russian Brides”. The work is meant as a contribution to the discourse around foreign workers in the Netherlands and a critical reflection of the respective immigration policies.

14. Mediamatic Russian Brides, 2008

Christin Lahr initiates a market for the exchange of personal data as a critical work on privacy issues in the internet. A market place for the redistribution of cultural capital may the community project http://www.1kg.org be considered. Travelers through China can volunteer to transport educational material to remote areas. The platform helps to coordinate supply of volunteers and demand for books etc. The work, though not exactly produced with artistic intention was awarded at the Ars Electronica in 2005. The project “Open-Clothes.com” envisions a platform for all transactions and interactions around the design and distribution of customizable clothes and won also an Ars Electronica award in 2004.

For these artistic markets the principles of web 2.0 internet economy seem to apply. As the ideal media to match niche demand and niche supply (Anderson 2006) these markets become niche products themselves, often defying their lack of liquidity. Collages of transactional modules may be meshed-up in this art form; they may be even considered online business models or even value chains of online businesses. The” Google Will Eat It Self” project already displays these features.

An actually functioning real time market running over years have the art group Derivart installed in the centre of Barcelona. Deviant Art founded Bar Bolsa, a pub in which the prices for alcoholic drinks fluctuate according to demand. With rising amount of orders for a certain brand of beer this brand’s price increases and the fluctuating values are displayed in real-time on screens, similar to a stock exchange. The artists label this artwork as “finance art”. Their name “Derivart” is by a class of financial instruments, so called derivatives, Their aim is to explore the “the intersection of art, technology and finance.”

15. Bar La Bolsa, Barcelona, since 1997

Art reflecting Finance

Finance is considered the “brain of an economy” and as a service sector facilitates the allocation of capital. The mechanisms of risk and reward, investing and speculation have interested artists since Duchamp, as we saw earlier. There are self-referential artworks, reflecting on the market-value of artworks, such as Sabine Gross displays the most valuable artists of the art market in a chart (“Wertsteigerung” (Increased Value), 2005). However, here we investigate artworks, where the artist himself actively participates in the financial markets.

Investing and Online Trading

An attempt to speculate with some cultural funds was undertaken by American artist Robert Morris in 1969. He proposed that the Whitney museum provide a small amount of money to invest in what he called blue “chip art” works which he was proposing to sell in Europe at higher prices and thereby profit the museum. The museum’s trustees however resisted this idea and considered it as too risky. They made Morris to invest in “risk-free” assets, such as Treasury bonds.The artwork consists of the correspondence Morris and the trustees and discussed refers to notions of risk.

Relying on his expertise as a non-professional stock trader, artist Michael Goldberg played the stock market for three weeks from a gallery generating charts and other forms of data visualization as output. He had built a form of “strategic interface” to the online market in the form of a tower. Goldberg had raised 50.000 AU$ from befriended investors, traded without personal risk and closed with a 1000 AU$ loss.

16. Michael Goldberg, Catching a Falling Knife, 2002

Goldberg seems relatively secretive about his expertise, thereby potentially imitating the discreteness of the financial services industries and positioning himself as part of both, the artistic and the financial context. To have an opportunity to witness the value creation through the supposedly secretive know-how of day-trading is potentially the aesthetic gain for the gallery visitors.

Conclusion: Transactional Arts – Art with Incentives

Many interactive art works make use of interactive media in a transactional way and transfer values. The artists take seldom profit and in case of financial gains they are often deliberately given away. This may be part of the aesthetic heritage to 18th century aesthetics and the requirement of the disinterestedness of the aesthetic judgment.

The transactions involve various forms of capital, e.g. aesthetic, cultural, social, financial capital. The aesthetic success of a transactional artwork seems not to depend on a successful transaction. So, even in the cases of unanswered auction art offers and illiquid markets – one may argue in favor of transactional art –the aesthetic value of these works is not diminished.

Artists using interactive media design possibility spaces. Artists using transactional media work additionally with incentives. As governments steer the behavior of their citizens e.g. with tax incentives, artists now facilitate and/or execute transactions as part of their work. They craft deals and foster the exchange of values. Sometimes they design decision architectures where they may “nudge” participants into desired behaviors.

The social positioning of agents involved plays an important role in transactional art. Their actual negotiation power becomes a constituent of the artwork. Therefore transactional artworks are always “aspectual” and relative to the social positions of the agents involved. The characteristic of variability of interactive media and transactional media may haul this kind of art.

Artists reflect their negotiation power in various ways, often with an audacious gesture of self-empowerment. The artist often creatively circumvents the weaknesses of his social position and claims the possession or creation of fictitious values. As demonstrated by Duchamp, non financial value were successfully exchanged for other forms of capital and generated, besides the artistic merits, financial profits for the artist.

Often transactional artists provide a meta-platform for others to post their offers and demands or even design incentive-structures. In this sense, transactional art leads to meta-art works enabling creations by others (and other artists).

Since many transactional artworks involve deal-making, an element of rationality is characteristic for the interactions taking place. Whoever the counterparty is, she has to accept the offer preceding the transaction. Therefore transactional art involves a kind of agreement or contract which may be implicitly or explicitly stated. The core function of contracts is to organize the transfer of values; therefore it is not surprising that transactional artist actually reflect this kind of social agreement. The proposed deals have to appeal to the value systems and rationality of the participants, even if they come from different social contexts. This may be seen as a refreshing alternative to the proven artistic strategies of the dysfunctional and absurd.

As a highly interdisciplinary art form, transactional art offers insights in how disciplines may inform each other and how interdisciplinary works are actually judged by the contributions they make to all disciplines involved and to what extend they fulfill the success-criteria in the different domains.

Many of the transactional artworks we saw spell out a radical critique of capitalistic principles. With the development of the internet as a transactional medium and its reflection by artists there may be future potential for more constructive explorations of social interactions in general and capitalism in particular. Transactional art may be highly demanding to its participants but – since always situated within the contexts of economic resources and spheres of power – could reward society with some valuable insights.

References

C. Anderson, The Long Tail, Random House Business Books, 2006

B. Arikan, http://burak-arikan.com/

R. Atkins, Art as Auction, http://www.mediachannel.org/arts/perspectives/auction/index.shtml